Ocean Temperature Rise

Of all the excess heat that results from people’s emissions, 93.4% goes into oceans. Accordingly, the temperature of oceans has risen substantially.

NOAA analysis shows that the most recent 12-month period, November 2013–October 2014, broke the record (set just last month) for the all-time warmest 12-month period in the 135-year period of record. The global oceans were the warmest on record for October. For January–October, the average global sea surface temperature was also record high.

The danger is that ocean temperatures will continue to rise, especially in the North Atlantic, and that the Gulf Stream will keep carrying ever warmer water from the North Atlantic into the Arctic Ocean, threatening to unleash huge methane eruptions from the Arctic Ocean’s seafloor, in turn causing even higher temperatures and more extreme weather events, wildfires, etc.

High Methane LevelsHigh methane levels were recorded over the Arctic Ocean in October, as discussed in

this earlier post, and were sustained in November, as discussed in

this post. Methane levels as high as 2717 ppb were recorded on November 16, 2014, p.m, by the MetOp-1 satellite at 469 mb (i.e. 19,820 ft or 6,041 m altitude), as the image below shows.

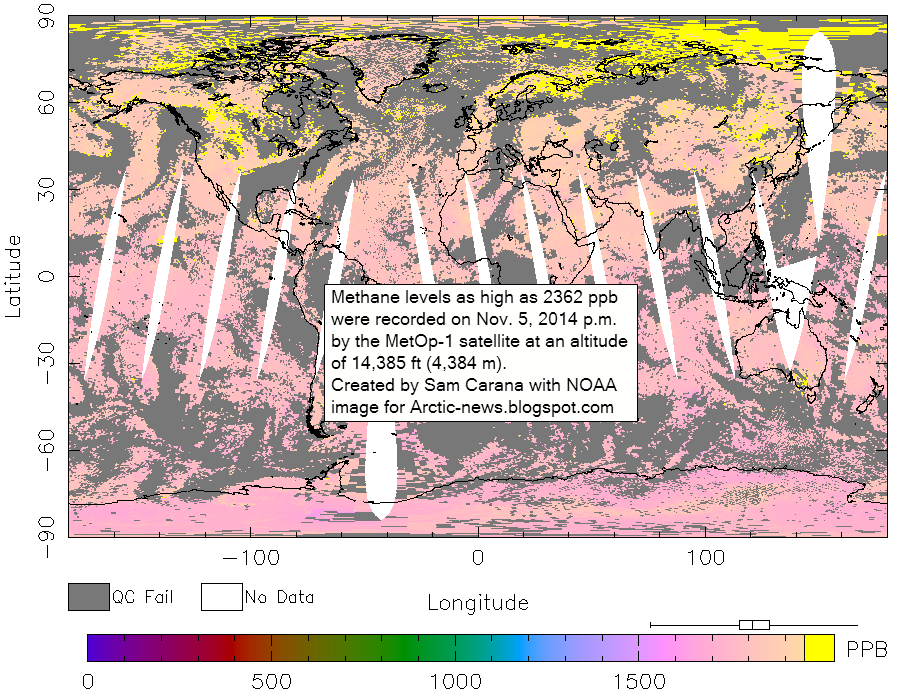

Methane levels as high as 2549 ppb were recorded on November 19, 2014, p.m, by the MetOp-2 satellite at 586 mb (i.e. 14,385 ft or 4,384 m altitude), as the image below shows.

Above image further confirms earlier indications that these high methane levels do indeed result from large methane eruptions from the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean.

Greenhouse gas levels in general are very high over the Arctic, as earlier discussed in a

recent post and as illustrated by the image below, showing carbon dioxide levels as high as 420 ppm at high latitudes, while the global mean was 403 ppm, on November 19, 2014, p.m., at 945 mb (i.e. 1,916 ft or 584 m altitude).

As said, sustained instances of large abrupt methane eruptions from the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean threaten to strongly accelerate warming in the Arctic even further, in turn resulting in ever more methane being released, as illustrated in the image below, from

an earlier post.

|

Self-reinforcing Feedback Loops

Such methane eruptions are part of a number of self-reinforcing feedback loops that can strongly accelerate warming in the Arctic. Above image, from an

earlier post, illustrates two such feedbacks, i.e. albedo changes due to snow and ice demise, and methane releases. Further feedbacks are described in

this post and

this post, and in the image below.

The threat is that such rapid temperature rises will appear at first in hotspots over the Arctic and eventually around the globe, while also resulting in huge temperature swings that could result in depletion of supply of food and fresh water, as further illustrated by the above image, from an

earlier post, and the image below, from another

earlier post.

|

| [ click on image at original post to enlarge ] |

IPCC warnings not strong enough

In above paragraph, the IPCC warns about the risk of methane eruptions from the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean further accelerating global warming. While the IPCC does model for a temperature rise that could exceed 12 degrees Celsius in a ‘business as usual’ scenario (i.e. without action taken), the IPCC does not anticipate that such a rise could occur before the year 2250, as illustrated by the image below.

The situation could be much worse than foreseen by the IPCC, due to a number of reasons, including:

- The non-linear way feedbacks can hugely increase temperature rises.

- The IPCC’s underestimation of the amount of methane contained in sediments under the Arctic Ocean and prone to be released as temperatures rise. Shakhova et al. estimate the accumulated methane potential for the Eastern Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS) alone as follows:

- organic carbon in permafrost of about 500 Gt;

- about 1000 Gt in hydrate deposits; and

- about 700 Gt in free gas beneath the gas hydrate stability zone.

Back in 2008, Shakhova et al. considered release of up to 50 Gt of predicted amount of hydrate storage as highly possible for abrupt release at any time.

Furthermore, mantel methane could add to our predicament, as discussed in an earlier post. - Back in 2002, Malcolm Light already warned that seismic events could trigger destabilization of methane hydrates. Furthermore, huge temperature swings can combine with pressure swings and storms, and with swings between expansion and contraction of soil and ice, resulting in severe shocks to ecosystems, as described in an earlier post.

- The IPCC’s ignoring of large methane eruptions from the seafloor of the Arctic Oceans and the resulting growth of mean global methane levels at higher altitudes, as discussed in an earlier post.

Steven Sherwood et al. wrote

back in 2010 that peak heat stress, quantified by

wet bulb temperature, across diverse climates today never exceeds 31 degrees Celsius (see also this

update). Some may believe that this doesn’t apply to the Arctic and the higher altitudes in mountain regions. However, at the June Solstice the amount of solar radiation received in the Arctic is higher than anywhere else on Earth, An increased occurence and intensity of heatwaves could expose large areas of the Arctic and mountain regions to sustained heatwaves exceeding peak heat stress temperatures. In addition, ocean acidification and

oxygen depletion in the Arctic Ocean would make it hard for fish, seals, polar bears and further wildlife to survive. Furthermore, the short growth season combined with a long, cold winter limits vegetation in the Arctic, while ecosystems are also becoming increasingly exposed to wild weather swings and wildfires.

Risk AssessmentWhen taking above points into acount, an absence of action seems to guarantee human extinction by the year 2050. Little action will be ‘too little, too late’ and will merely delay human extinction by a few years, as illustrated by the graph below.

The graph identifies the years 2030 and 2040 as critical. Beyond the year 2030, the risk that humans will go extrinct grows larger than 1% in the absence of action. By the year 2040, the risk of human extinction will have increased substantially, especially if no action will have been taken, but also if too little action will have been taken up to 2040, while even with the best possible programs put in place by the year 2015, there will be a 2% risk of human extinction by 2040, e.g. due to war over what action to take, or due to political opposition or errors making such programs ineffective or even counter-productive.

In conclusion, it is highly likely that the risk of human extinction already now is intolerably high and rising with every moment passing with little no action taken to reduce the risk. This calls for comprehensive and effective action, as further discussed at the

Climate Plan blog.

References- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) WGI Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), Final Draft (7 June 2013), page 168.

http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGIAR5_WGI-12Doc2b_FinalDraft_Chapter02.pdf- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) WGI Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), Final Draft (7 June 2013), Figure 12.5.

http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/uploads/WGIAR5_WGI-12Doc2b_FinalDraft_Chapter12.pdf- An adaptability limit to climate change due to heat stress - by Steven C. Sherwood & Matthew Huber

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2010/04/26/0913352107.full.pdf- Ocean Temperature Rise - by Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/10/ocean-temperature-rise.html- Methane release from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf and the Potential for Abrupt Climate Change - by Natalia Shakhova & Igor Semiletov

http://symposium2010.serdp-estcp.org/content/download/8914/107496/version/3/file/1A_Shakhova_Final.pdf- Anomalies of methane in the atmosphere over the East Siberian shelf: Is there any sign of methane leakage from shallow shelf hydrates? - by Shakhova, Semiletov, Salyuk & Kosmach

http://www.cosis.net/abstracts/EGU2008/01526/EGU2008-A-01526.pdf- Mantle Methane - by Malcolm Light

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/02/mantle-methane.html- Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes - by Jennifer A. Francis and S.J. Vavrus, in: Geophysical Research Letters 39 (6):.

doi:

10.1029/2012GL051000http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2012GL051000/abstract- Near-Term Human Extinction - by Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/04/near-term-human-extinction.html- Warm waters threaten to trigger huge methane eruptions from Arctic Ocean seafloor - by Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/08/warm-waters-threaten-to-trigger-huge-methane-releases-from-arctic-ocean-seafloor.html- How many deaths could result from failure to act on climate change? - by sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/05/how-many-deaths-could-result-from-failure-to-act-on-climate-change.html- Methane linked to Seismic Activity in the Arctic - by Malcolm P. Light & Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/seismic-activity.html- Wild Weather Swings - by Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/10/wild-weather-swings.html- Four Hiroshima bombs a second: how we imagine climate change - by Sam Carana

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2013/08/four-hiroshima-bombs-second-how-we-imagine-climate-change.html- Polar jet stream appears hugely deformed

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2012/12/polar-jet-stream-appears-hugely-deformed.html- Near-Term Human Extinction

http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/2014/04/near-term-human-extinction.html